Inconsistent Utility & Arbitrage

Your Utility Function is Less Rational Than You Think

Our utility preferences often defy strict rationality because human decision-making is influenced by psychological factors, especially when dealing with uncertainty and risk. These tendencies are some of the key insights of prospect theory, developed by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. In this short post, we illustrate an example where the reader will be presented with a mathematical proof of the irrationality of their choice and yet will be unlikely to change the decision that they make.

A Simple Preference Test

Consider the following two choices:

(A) 1% probability at winning $10 Million

(B) 0.8% probability at winning $20 Million

Most readers will likely choose B. Now, consider the following two choices:

(A) 100% probability at winning $10 Million

(B) 80% probability at winning $20 Million

Most readers will now likely choose A. We argue that choosing different letters in the two above scenarios are logically inconsistent (it would be consistent to choose AA or BB but not AB or BA). WLOG let your preference be BA and let your utilities for winning $10 Million and $20 Million be U(10M) and U(20M) respectively, then:

0.01 U(10M) < 0.008 U(20M) ⇔ 1 U(10M) < 0.8 U(20M)

Moreover, this result holds for ANY utility function (the utility function itself doesn’t even need to follow common-sense restrictions such as risk aversion).

The inconsistency of preferences leads to possible arbitrage. Consider a scenario where you have been given the chance to choose between

(A) 1% probability at winning $10 Million

(B) 0.8% probability at winning $20 Million

and you choose (B). Now, the probability is realized by rolling a 100-sided die (numbered 1 to 100), followed by a 10-sided die (numbered 1 to 10). The first roll needs to be a 1 in order for you to move on.

Assume you are very lucky, and the 100-sided die lands on a 1 upon its roll. The gamemaster now gives you a choice, you can either (A) pay him a small amount of money at which point you are guaranteed to win exactly $10 Million, or (B) you roll the 10-sided die and win $20 Million if it lands between 1 and 8 inclusive, but otherwise you get nothing if it lands on 9 or 10.

If your preference was BA, then you’d pay the gamemaster money and go for the same route. However, if you knew that you’d make this choice given a lucky roll of the 100-sided die, your initial preference should have been AA instead, and you could have avoided paying the gamemaster.

We note that the gain in optionality (the choice to pay the gamemaster to switch preferences) would lower the expected utility you receive from the game (by the amount you value the payment to the gamemaster times the probability you pass the first die roll) if and only if you had inconsistent preferences. If your preferences were consistent, the gaining of optionality should not lower the utility of the game.

The Preference Test in Markets

The reader may at this point consider the game contrived, but there are real-life scenarios which are not too dissimilar.

For example, a venture capital firm has a very low probability (e.g., 0.8% to 1%) of identifying and investing in a unicorn startup (a privately held startup valued over $1 billion). Assuming that the firm is lucky (make no mistake that luck is required in this endeavor as much as skill is), the VC must decide how to exit; it can either sell shares in the secondary market to ensure a smaller but guaranteed return, or wait for the company to go public, aiming for a higher payoff but much higher risks.

Founders also face exit decisions. While they might dream of taking their company public, they may choose an acquisition or a strategic merger for a safer, guaranteed return. This decision often involves balancing the security of a smaller exit (e.g., acquisition) against the risks and rewards of continued growth or an IPO. Many founders feel this dilemma intensely, especially if they’re emotionally invested in their company’s vision and independence.

Indeed, as firms mature, founders often start considering their personal financial security, especially if much of their wealth is tied up in company equity. The lure of a liquidity event—whether through a partial buyout or secondary market sale—becomes appealing. Founders may prioritize this certainty over the potential (but riskier) gains from holding onto the business longer. Investors in the form of acquiring firms or PE firms can capitalize on this preference shift by offering a partial buyout or creating a structured deal that allows founders to cash out some of their equity. This lets investors acquire a larger stake or even majority control at a potentially favorable price, taking advantage of the founder's new preference for security and liquidity.

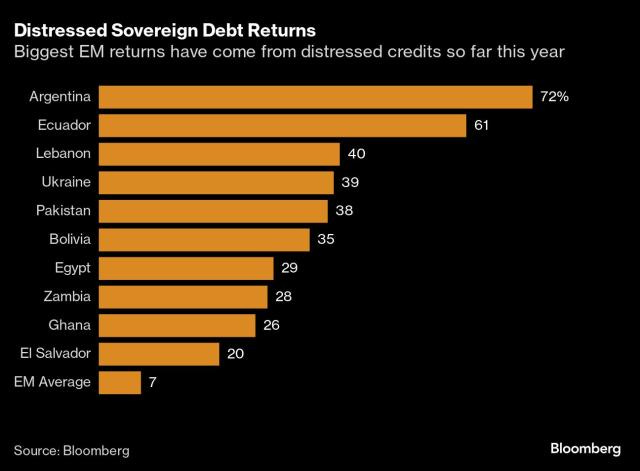

Taking advantage of this sort of inconsistent preference (or something similar) can be seen in some other trades as well. For example, creditors holding distressed debt may vacillate between wanting to wait for a higher recovery (riskier but potentially more lucrative) and accepting a guaranteed but smaller recovery to exit a challenging position. Investors specializing in distressed debt can step in to buy these securities at a discount, benefiting from creditors’ preference for certainty. Distressed debt funds capitalize on this inconsistency by acquiring assets cheaply, restructuring them, and eventually realizing a higher return when they recover or get refinanced.

Another example is that in merger arbitrage, inconsistent preferences often appear around timing and certainty in deal progress. Shareholders in target companies may show a preference for certainty when a merger is announced, especially if the premium is guaranteed. However, as deals progress and uncertainties arise (regulatory review, financing, etc..), some shareholders may reverse preferences, prioritizing a near-certain, smaller gain (by selling early) over a higher but riskier future payoff if the merger succeeds. Merger arbitrageurs can step in, buying shares from these investors at a discount. They benefit from the opportunity to hold out for the higher payoff, knowing they are compensated for bearing the uncertainty. This approach effectively allows merger arbitrageurs to exploit the price discrepancy created by inconsistent preferences among investors, capturing the spread once the deal closes successfully.

It’s important to note that being risk-averse isn’t irrational in itself; in fact, it’s a reasonable preference that many individuals and institutions hold. Risk aversion allows for stability and predictability, especially in scenarios where consistent, guaranteed returns are prioritized over speculative gains. Likewise, those with a higher risk tolerance often take on uncertain investments in hopes of realizing larger returns. However, the purpose of this discussion is to highlight how, in the real world, risk preferences often shift over time or due to changes in circumstances. For instance, individuals who once tolerated high risk may, later in life, prioritize security over potential gains. This shift in utility functions opens up unique opportunities for arbitrageurs and specialized investors. By capitalizing on these evolving preferences, they can achieve uncorrelated returns in fields like venture capital, merger arbitrage, and distressed debt, where investments with mispriced risk-reward profiles arise.

Disclaimer

The information provided on TheLogbook (the "Substack") is strictly for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered as investment or financial advice. The author is not a licensed financial advisor or tax professional and is not offering any professional services through this Substack. Investing in financial markets involves substantial risk, including possible loss of principal. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The author makes no representations or warranties about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability of the information provided.

This Substack may contain links to external websites not affiliated with the author, and the accuracy of information on these sites is not guaranteed. Nothing contained in this Substack constitutes a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments. Always seek the advice of a qualified financial advisor before making any investment decisions.